What Is WIFIA’s FCRA Budgeting Issue?

The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act Amendments of 2022 is expected to be reintroduced in Congress soon. This short bill contains various amendments and directives that will improve the US EPA’s WIFIA Loan Program, especially for the efficient implementation of the Army Corps’ recently funded section of WIFIA, the Corps Water Infrastructure Financing Program.

Most of the provisions in the bill are straightforward. However, one amendment stands out as a bit arcane. It involves the federal budgetary treatment of WIFIA loans under the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA). FCRA treatment requires a federal loan program to utilize something akin to accrual accounting for loans instead of the cash-based budgeting used elsewhere by the federal government. This results in far more realistic reporting and has effectively been standard operating procedure for all federal loan programs since FCRA was enacted.

Why is long-established FCRA treatment now an issue at WIFIA, a successful program with a solid track record of efficiently executing high-quality, low risk loans? The answer involves a new, but increasingly important area of lending for WIFIA and other federal infrastructure loan programs: loans to projects with some degree of federal involvement.

Example: Financing a non-federal share in a federally involved project

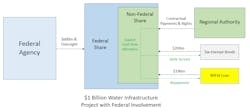

Imagine an infrastructure project for large-scale water management, like flood control or dam rehabilitation. The optimal scale of the project for both national and regional benefit is about $1 billion. For various reasons, a federal agency will be involved in overall project construction and management. But the agency can only allocate $600 million to the specific project.

A regional water authority recognizes the importance of the project for the communities within their jurisdiction. The authority agrees to provide the $400 million balance so the project can be completed at the optimal scale, which is especially important for regional benefits. Such cost-sharing is clearly a win-win-win for national infrastructure, federal taxpayers, and regional communities.

The authority cannot write a lump-sum check for the $400 million, and in any case, it wants a long-term contractual agreement with the project that specifies all its rights and obligations in detail. The authority will make periodic payments under this contract to cover its share of operations and maintenance, and most importantly, it will provide cash flow for servicing $400 million of long-term debt to fund the construction cost balance. There is nothing unusual here. Such contractual arrangements are standard in project financing.

The authority will fund the contractual payments by a combination of general and special taxes, water rates, and other revenues from the regional communities that will benefit from the project. This source of funding has a high level of creditworthiness, which gives the authority several financing options.

First, it considers issuing tax-exempt revenue bonds. Bond credit rating will be based primarily on the authority’s ability to make contractual payments from regional taxes and the project’s explicit cash-flow allocations. An investment-grade rating is confidently expected. Bond tax counsel notes the Federal Agency’s involvement in the project and confirms that the federal government is not providing a direct or indirect guarantee of bond debt service, per IRC Section 149 (b).

Next, the authority looks at the WIFIA loan program. The project is statutorily eligible in every way, and although the Treasury-based interest rate is not too different than tax-exempt bond yields, WIFIA loans offer various interest rate management and term features that are especially important for large-scale, long-lived projects. A WIFIA loan is, however, limited to 49% of “project” cost, which in this case means 49% of $400 million, or $196 million, because that represents the authority’s share of the full project. Fortunately, tax-exempt bonds and WIFIA loans are easy to combine and are effectively complementary, so the authority settles on a two-tranche financing plan for its share, $204 million of bonds and a $196 million WIFIA loan.

All sounds good, right? No. The authority’s WIFIA application is rejected at the outset because the Office of Management & Budget’s 2020 criteria for federally involved projects will classify the entire project as "Federal". According to OMB, any WIFIA loan determined to be for a "Federal Project" will necessarily entail a "federal borrower", regardless of the repayment source. Since FCRA budgeting is statutorily available only for loans to "non-federal borrowers", a WIFIA loan for the regional authority’s share of the project cannot receive FCRA treatment, according to OMB, and is therefore ineligible.

OMB’s decision is a stark outlier in the context of project facts. If the authority simply wrote a $400 million check, that would be a valid cost-share and excluded from the federal cash-based budget. Any private-sector, non-recourse project financing that the authority arranges for its share would not be consolidated into the federal agency’s budget. And tax-exempt financing — another form of federally subsidized debt — for the share clearly relies on a third-party determination that the substantive borrower is the non-federal authority, not the federal agency.

Still, OMB’s criteria, however inconvenient with respect to infrastructure policy outcomes or statutory loan program eligibility, must be correct, right? Perhaps not.

The fundamental flaw of OMB’s 2020 FCRA Criteria

WIFIA’s FCRA criteria for federally involved projects were developed in response to a Congressional directive inserted in a consolidated appropriations bill at the end of 2019. WIFIA had received a few applications from such projects, and more were expected, especially as the implementation of the Army Corp’s CWIFP section of WIFIA was imminent.

The criteria were intended to clarify FCRA law, which simply defines a FCRA loan as one “…to a non-federal borrower under a contract that requires the repayment of such funds…”. To provide context for this succinct definition, Congress directed OMB to develop criteria based on FCRA law and the recommendations of the 1967 Report of the President’s Commission on Budget Concepts which outlines the fundamental principles behind what became FCRA law in 1990.

FCRA law would benefit from a clarification for loans to projects with some federal involvement. Potential loan program applicants could then self-screen their applications and possibly modify the proposed loan structure to ensure that FCRA treatment will be available.

3 ways the OMB criteria miss the mark

But the criteria OMB published in the Federal Register in 2020, apart from leading to odd results as described in the illustration above, do not appear to be compliant with the Congressional directive’s clear requirements, in three ways.

-

The 2020 OMB criteria are not ‘criteria’ but rather are primarily a series of questions that imply the criteria that OMB will apply offstage. This non-transparent approach would appear to be inconsistent with the primary intent of the Congressional directive. OMB is entitled to ask questions — no directive is required for that — but what is needed are the principles and explicit criteria by which the answers will be interpreted. That was the point of the directive.

-

The 2020 criteria are not primarily based on FCRA law. That law is very narrowly focused on federal credit financial assets and their budgeting, not the use of loan proceeds, which is governed by individual program statutes and rules. Instead, OMB appears to have broadly repurposed the criteria to determine whether a federally involved project is a "Federal Project" or not. While that might be interesting for some federal reporting purposes, it is not a concept found in FCRA law. OMB then conflates a "Federal Project" with a "federal borrower", meaning that all "Federal Projects" will automatically run afoul of FCRA’s exclusionary definition. In contrast, a multi-party "Federal Project" — however vaguely or arbitrarily defined — may well include a substantive "non-federal borrower" per FCRA when a non-federal project participant has the obligation to repay the loan. What better determination of a substantive borrower than the entity that agrees to be on the hook for repayment?

-

The 2020 criteria are not based on the relevant recommendations of the 1967 report. Yes, one budgeting principle from the 1967 report is explicitly stated, from Chapter 3, that ‘‘borderline agencies and transactions should be included in the budget unless there are exceptionally persuasive reasons for exclusion.’’ Undoubtedly this is a valid prudential concept, however it is completely irrelevant to the FCRA issue. Anything and everything that a thoroughly federal program like WIFIA does – especially its lending activities – will indisputably be included in the federal budget. The actual issue is whether a program loan belongs in the cash-based bucket or the FCRA bucket. Chapter 5 of the 1967 Report, which is unambiguously titled "Federal Credit Programs" describes FCRA’s founding principles very clearly and in detail. The primary principle outlined is that federal loans require special budgeting treatment due to a substantive obligation for repayment from non-federal sources – something that is echoed in FCRA law’s definition of a FCRA loan.

There are other problems. OMB included two footnotes to the 2020 Federal Register publication that simply exclude all loans to projects with Army Corps or Bureau of Land Management involvement from FCRA treatment, regardless of the facts of individual loan applications. There are no references to FCRA, WIFIA or other statutory bases for this blanket exclusion. It is not consistent with the principles of Chapter 5 of the 1967 Report nor within the scope of the Congressional directive.

The 2020 criteria appear to be flawed. As such, they will produce flawed results that are inconsistent with Congressional intent for both FCRA clarification and federal loan program policy objectives, as the above illustration shows. They should be rescinded as non-compliant with the specific requirements of the Congressional directive.

The WIFIA FCRA amendment

With the background outlined above, the purpose of the FCRA amendment in the soon-to-be-reintroduced WIFIA bill becomes clear: to address the confusion and erroneous results caused by OMB’s current criteria. The amendment is a simple statutory clarification that FCRA treatment of WIFIA loans will be available when the “dedicated sources of repayment of that [loan] are non-Federal revenue sources”.

Unlike OMB’s criteria, this approach is consistent with FCRA law, the principles outlined in the 1967 Report and the policy objectives of the WIFIA loan program. Perhaps some refinements to the language or additional definitions will be required before becoming law, but as it is, the amendment establishes the correct framework for a true clarification of the issue. It is also worth noting that the amendment is more consistent with the Congressional directive than OMB’s 2020 criteria.

The implications of WIFIA’s FCRA amendment go beyond the specific issue itself. WIFIA and other federal infrastructure loan programs will play an increasingly important role in U.S. public infrastructure renewal. To meet that challenge, the programs will need to expand in terms of both size and scope. As they do, there’ll inevitably be subtle and complex issues that require clarification and resolution, just as the FCRA budgeting issue arose when WIFIA’s applicants began to include federally involved projects.

When oversight agencies appear to get it wrong, infrastructure loan program stakeholders must actively respond and propose alternatives and improvements. WIFIA’s FCRA amendment serves as an excellent precedent for that critical process in infrastructure loan program development.