UW-Madison Study Explores Effectiveness of Rain Gardens

Vegetation plays a lesser role than other factors in how well rain gardens manage storm water runoff, according to the research of University of Wisconsin-Madison horticulture professor John Stier and graduate student Jake Schneider.

Since their study began in October 2005, there has been little difference in the performance of rain gardens planted with prairie species versus those sporting a lawn of common turfgrasses. Rather, construction parameters, including garden size and the presence of a water-retaining berm, appear to be important factors.

“What we’ve found so far is that berms are the main factor controlling runoff,” Schneider said, whose award, the Terry and Kathleen Kurth Wisconsin Distinguished Graduate Fellowship, supports the work, according to University of Wisconsin-Madison News. “I think the bottom line is that if you put in a rain garden as a catch basin, it’s going to be incredibly effective, no matter what type of vegetation you have.”

According to Schneider, native prairie plants, whose deep root systems reportedly help water permeate the soil, are supposed to produce the best rain gardens. He and Stier wanted to test this claim to see how turfgrass would compare.”

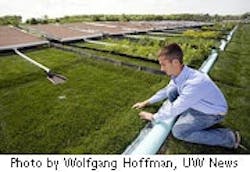

At the O.J. Noer Center, UW-Madison’s turfgrass research facility, Schneider built 16 rain gardens to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources specifications, each of which receives drainage from a 200-sq-ft section of rooftop. Four of the eight gardens he sodded with turfgrass also are surrounded by a 6-in.-high berm; the other four are not. The same goes for the eight gardens planted with a mix of prairie species.

Since Schneider began monitoring the plots a year and a half ago, the bermed gardens have consistently produced less runoff and allowed greater volumes of water to penetrate the soil. Vegetation type, in contrast, has shown little or no effect. Although don’t know conclusively why this is, Schneider and Stier suspect it relates to plant density, according to University of Wisconsin-Madison News.

As water quality is also a concern, Schneider and Stier won’t know the full story until analyses of nitrogen and phosphorus in the runoff and soil leachate are complete. When present at excess levels, these nutrients act as major water pollutants.

Source: University of Wisconsin-Madison News